All Dolled Up: Playing With the Dolls of Special Collections

What is A Doll?

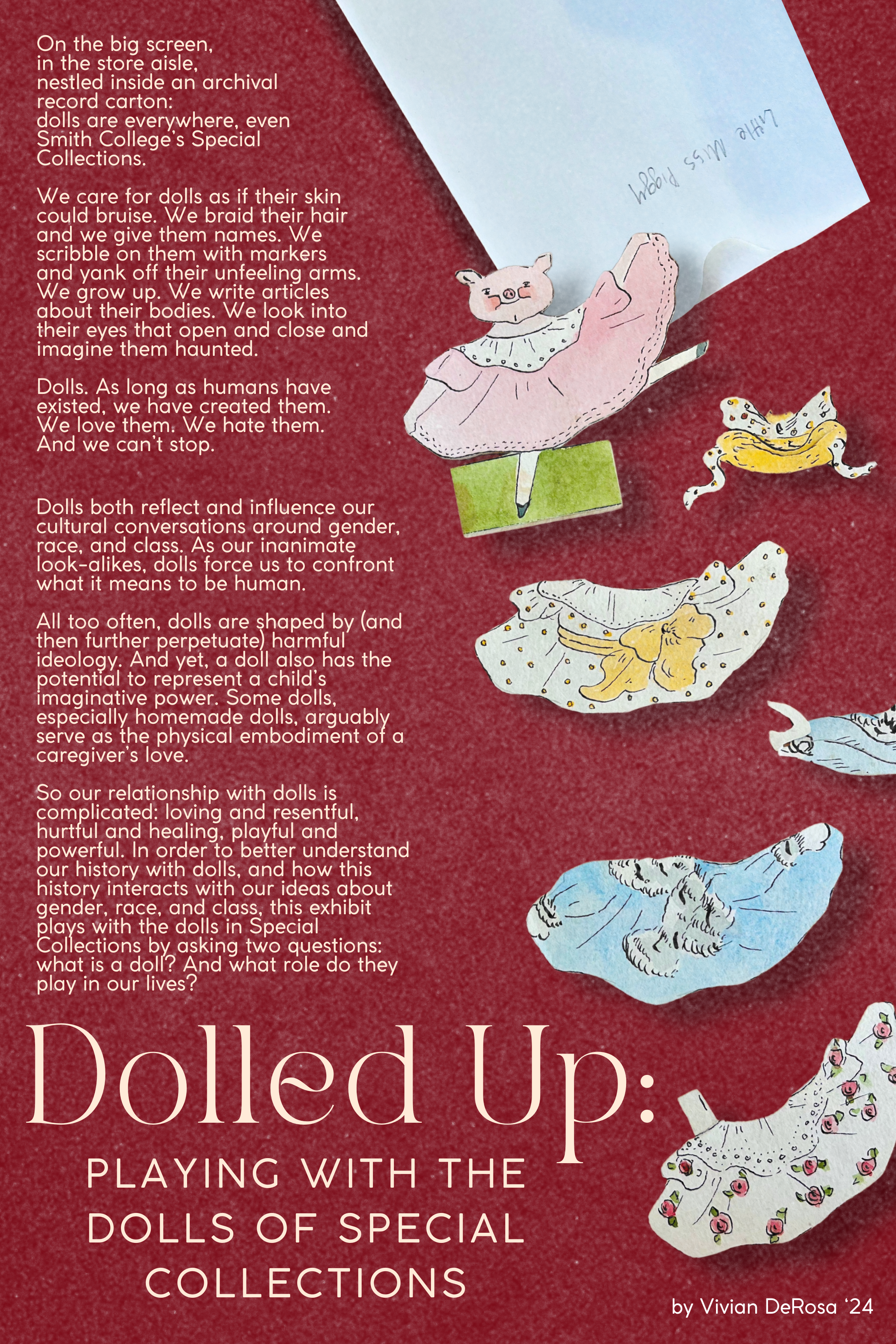

A rag doll, stitched together for a child by someone who loves them. A dress-up doll composed of computer pixels, who exists only as long as the website tab remains open. A paper doll made with colored pencils and an old Costco receipt. A fragile bisque doll, a doll made of sticks, and yes — a Barbie, an American Girl, a Bratz.

What makes a doll a doll?

These dolls from Special Collections offer just a glimpse of the different shapes a doll might shape — from paper to cloth, handmade to mass-produced. Some were made for children, some for adults. The only similarity that unites them all? These dolls all have human figures, but none of them are alive — which means that when we ask, “What does it mean to be a doll?,” we are also asking, “What does it mean to be human?

Paper doll family made by "Mommy and Aunt Sylvia”

1900

Miscellaneous Subjects Collection

SSC-MS-00392, Box 5, Folders 5-9

Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History

Do you have a pencil and paper? Pretty soon, you could have a doll. Paper dolls are easy to create, portable, and playable — they were a fan favorite in the early 20th century. Not many have survived, but that only testifies to how extensively children played with them. Perhaps paper dolls offer what captivates us most about dolls: the fantastical possibility of what we might wear, what life we might have, who we might become.

Hand-sewn dolls

(circa) 1973

Therese Weil Lansburgh papers

SSC-MS-00090, Box 5, Folder 9

Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History

Rag dolls like these hand-sewn friends have a special place in doll history. Rag dolls are, by definition, any doll made from scraps, which means that for most of history they have been the most accessible doll.

For example, in the 19th-century, enslaved and working-class girls who did not have access to expensive dolls would still have likely had a homemade rag doll. In a world in which children were unjustly treated as laborers, dolls became more than just a toy: they were an opportunity for girls to prioritize their own play.

Class of 1909 and Class of 1929 Reunion Dolls

1954

Smith College Archives artifacts collection

CA-MS-01118, Box 5

Smith College Archives

These class reunion dolls were created in order to celebrate the class of 1909’s 55th reunion and the class of 1929’s 20th reunion — but they are also a perfect example of the pitfalls that come with representing a diverse group of people with a singular doll. What might these dolls suggest a Smith student looks like? White, slight, feminine, and perpetually youthful? This inaccurate and harmful implication of who could be a Smith student in the early 20th-century might help us understand how dolls have made people feel othered or unwelcome.

Sophia Smith Change Dolls

Undated

Smith College Archives artifacts collection

CA-MS-01118, Box 26

Smith College Archives

Some dolls take unusual shapes. These Sophia Smith “change” dolls were used by the Cleveland Smith Club as a fundraiser: as people donated their change, the dolls would “stand-up,” their bodies full of coins.

“Bangkok Dolls of Thailand” Catalog

1989-1992

Old Lesbian Oral Herstory Project records

SSC-MS-00669, Box 28

Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History

These dolls were created by Tongkorn Chandavimol, the founder of Bangkok Dolls. Chandavimol described her dolls as “miniature ambassadors for the culture and crafts of Thailand,” and each is made entirely of local materials with a hand-painted face.

Chandavimol points out the compelling contrast between the imaginative possibility a doll offers and the tangibility of the doll itself. Everything a doll possesses, whether that’s a face that never ages or a wardrobe full of clothes, is out of reach — and yet, you can hold a doll in your arms. As Chandavimol says, “It is like a dream, but a dream that is real. You can touch them.”

What Role Do Dolls Play in Our Lives?

Did you long to play with dolls, but couldn’t find a doll that looked like you? Did you face judgment from friends or family for wanting a doll? Did you treasure your dolls, which once belonged to your parents? Were you deeply afraid of American Girl Dolls because of their freaky little front teeth?

Our individual experiences with dolls vary — from negative to positive, universal to hyper-specific.

However, at the same time that we cultivate a relationship with dolls in our own lives, we also interact with dolls as symbols on a much larger scale.

Dolls have something to say about power. We compare ourselves to dolls when we feel powerless: “He treated me like a rag doll.” After all, dolls have no agency. They cannot move or think on their own.

And yet, dolls also offer power to a group of people with very little of it: children. Children do not get to decide what they eat or where they live, but they get to decide what happens to their doll. As Margo Jefferson writes in Black Dolls, “They do what they want with you. You do what you want with the doll.”

This power relationship only becomes more complicated when we consider gender, race, and class. Just think of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, in which Claudia, a young Black girl, takes apart and destroys the white baby dolls that everyone around her seems to idolize, literally deconstructing white supremacy.

Dolls are mirrors, reflecting us back to ourselves. And yet they are also active players in our cultural conversation. Dolls inform not only our past and our present, but our future.

“Healer of Broken Dolls. Esperanza and her shop. Havana, Cuba” photograph

1968

Diana Davies papers

SSC-MS-00309, Box 6, Folder 10

Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History

Esperanza introduces herself as the “Healer of Broken Dolls,” and she does not diminish the importance of her work — “I am a doctor.” Children brought their damaged dolls to Esperanza’s shop, where she fixed them for free. By regarding her own labor with respect, Esperanza acknowledges how essential dolls were. These dolls, perhaps given by a caregiver and now healed by the neighborhood doctor, represented to children the adults who loved them.

“Japan: Women at work, photograph of a woman and a man working at a small doll factory”

(Approximately) 1920

YWCA of the U.S.A. records, Record Group 9

SSC-MS-00324-RG9, Box 1011, Folder 11

Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History

Except for homemade dolls, dolls are products — made, bought, and sold. But who makes a doll impacts its life as a material object. For example, in the 19th century, doll wigs were typically made of working-class girls’ hair, which quite literally turned working-class girls’ body parts into toys for the upper class. For some people, dolls represent play, but for many others, dolls represent labor.

Children’s drawings and writing, responding to William’s Doll by Charlotte Zolotow

April 1974

Ms. Magazine records

SSC-MS-00362, Box 202

Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History

For an unpublished Ms. article, 4th, 5th, and 6th graders from Queens, N.Y. sent in drawings and short essays responding to William’s Doll, a book about a boy who wants a doll more than anything in the world.

Some children sent in their votes of approval — Lucas wrote that he thought “it’s all right” because he has a one-eyed octopus that he sleeps and plays with, while Madeline sent her blessing since her own sister wanted a dump truck toy (“and she had every right to want it”).

But not all the responses were as positive. One girl wrote that, “Boys should not have a doll because they will break it up. And pull off the head.”

Finally, one boy wrote: “I think Williams is a Sissy. Sissy and a Queer.”

Ad for “Victoria Ashlea Originals” in Dolls: The Collector’s Magazine

January 1992

Old Lesbian Oral Herstory Project records

SSC-MS-00669, Box: 28

Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History

Does this magazine ad creep you out? Don’t worry — you’re not the only one. Dolls are often the stars of our horror narratives. But why?

There’s the uncanny valley effect. Dolls look so realistic that it threatens our boundaries between human and nonhuman. Perhaps this ad’s tagline, “For the little girl in all of us,” hints at another terrifying possibility: dolls remind us of children who will never grow up.

But in horror movies, the fear often originates from yet another source — dolls’ access to children. Evil dolls threaten a parent’s ability to protect their children. This manifests in the literal (porcelain-doll- trying-to-kill-you-in-your-sleep) and the metaphorical (the interpreted threat that Barbie dolls pose to girls’ body image.)

Christmas Doll Tea Party photograph and ad

November 1951

Frances Bemis papers

SSC-MS-00016, Box 10, Folder 10

Sophia Smith Collection of Women's History

Tulle, bows, and flowers. A bride, a ballet dancer, a princess in a ball gown. Oh my! You would be forgiven for thinking this photograph feels like a parody of girlishness.

At times, dolls’ relationship with femininity is so flamboyant, flashy, and ridiculous that it borders on camp, opening the door to a queer reclamation of dolls. “Doll” is an in-group term of endearment for trans women and transfeminine people, while dolls like M3GAN and Barbie achieve gay icon status.

It is not a coincidence that the same dolls that scare us are also our queer idols— dolls that have the power to disrupt our preconceived notion of what is “natural” also have the power of queer potential, unafraid to imagine alternative possibilities of what our lives can look like.

Project People Foundation: Black Doll Project

1995-1997

Letty Cottin Pogrebin papers

SSC-MS-00294, Box 52

Sophia Smith Collection of Women's History

Under the apartheid in South Africa, Black dolls were banned, “a conscious attempt to undermine Black children’s pursuit of active, productive roles in South Africa's future.” Even after the apartheid ended in the early 1990s, Black dolls were extremely rare and expensive.

Linda Tarry, a Black American educator, collaborated with Helen Lieberman, a white Jewish South African activist, to found the Project People Foundation (PPF), which distributed 15,000 Black dolls to children across South Africa.

The importance of racial representation in dolls cannot be overstated — after all, the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case drew upon the Doll Test, the study of the psychological effects that segregation and racism had on Black children, demonstrated by how they interacted with Black and white baby dolls.

Dolls are the promise of possibility — who we might become. If dolls do not reflect our diversity, they do not offer a future worth imagining.